By: Rachel Robasciotti, Founder & CEO

Photo by Josh Appel on Unsplash

Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) funds have risen in popularity dramatically over the past decade, as has the demand for sustainable investments.1,2

In the last five years, as proliferation of ESG funds has increased further, we’ve also seen some discontent with ESG3 investing and a growing sentiment that many funds are simply using ESG as a marketing ruse – also known as “greenwashing” or “impact washing”.4

I’ve watched all of this develop alongside another, seemingly unrelated, fund trend – fee compression – and I believe these two issues are related.

Are well-intentioned investors and professionals unintentionally driving greenwashing by demanding low fees?

The short answer – Yes.

For a more in-depth answer, let’s look at the history and context.

History

How did we arrive where we are now with high market demand for “cheap ESG” products?

I believe the demands for both fee compression and for ESG stem from two separate tracks of recent investor discontent:

Track 1: Financial Discontent

Investors were rightly concerned that financial professionals were often grossly overpaid, and that financial products would often cost too much for the limited value they provided.

Track 2: Values Discontent

Investors saw that their portfolios and advisors were prioritizing only a financial return, sometimes at the expense of long term livability of the planet, and often at the expense of people directly impacted by portfolio companies’ actions.

The financial industry began to address both issues.

To address growing financial discontent, solutions came by way of fee compression and the proliferation of low-cost index funds; these funds require less human capital to run. Investment company mergers added additional scale and cost savings.

To address growing values discontent, socially responsible (which eventually became ESG) funds became broadly available.

Where I believe the investment industry made a mistake was in trying to address both problems using the same tools – you simply cannot proactively generate positive change as an investor and, at the same time, reduce human capital costs and expenses.

At Adasina, we manage JSTC, a deeply impactful exchange-traded fund (ETF), and I can tell you from direct experience that generating positive social change requires two major components that do not scale – people and data.

People: Understanding which changes investors should focus on because they would be most meaningful to impacted communities requires people to do community engagement. Similarly, getting public companies to change their behavior requires people to do shareholder engagement and mobilize other investors in the marketplace.

Data: Researching, discovering (sometimes creating), vetting, measuring, and translating non-financial data – that are not readily available – into valuable data for use in an investment portfolio takes extensive time, skill, money, and (again) people.

Neither of these critical components is scalable. Real impact requires real resources; you cannot do it well without additional resources.

And, if having real impact is important, our solutions must come from a new set of people – people from the communities most impacted by our investment decisions. People in positions of power are often blind to problems generated by their own systems – those in control of investment dollars are no exception to this rule. Currently, white men manage 98.6% of all investment assets.5 During the decades in which it was acceptable to charge high investment fees, the beneficiaries of those fees were overwhelmingly white men.

Ironically, at the very same moment the investment industry is responding to pressure to reduce fees, we are also experiencing a high demand for investments that generate genuine and significant positive social impact.

To generate real impact, we need to employ a set of people who haven’t traditionally been welcomed into the financial industry – women and those from Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) communities. Unfortunately, just as women and BIPOC folks are beginning to be welcomed into asset management, and gender and racial equity are emerging as critical themes in impact investing, the firms best equipped to do this work are underresourced. Women and BIPOC-owned asset management firms can be held back by building asset management firms in an environment of extreme fee compression and with statistically less personal wealth6,7, available to build our businesses.

For Systemic Problems, Look at The Systems

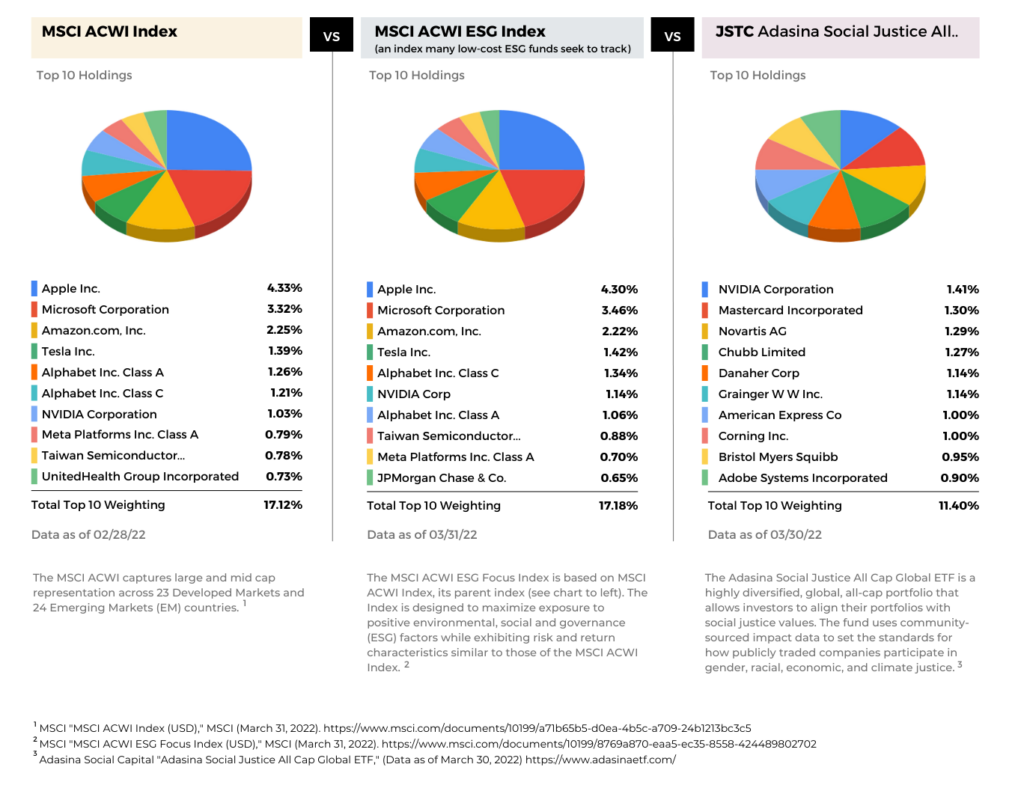

If we try to fix environmental and social problems cheaply, by using the systems and tools we already have (the same systems that brought us climate change, racial and gender inequity, and a vastly unequal wealth distribution), we will get investments that are inexpensive – but those investments will end up looking a lot like traditional investing and lack real impact. In the table below, I map out what I believe a typical low-cost ESG fund creation process might be as compared to a well-resourced process like Adasina’s, including an example that highlights how Adasina addressed a core gender justice issue. In the pie charts that follow the table, you can see how these different systems produce different outcomes.

Step | Example Cheap ESG (Does not represent any specific actual fund.) | Well-Resourced |

Let’s start an ESG/impact fund! How do we structure this product? | To be scalable, the fund should look and feel similar to our existing traditional investment products and comparable to competitors. | First, we consider the type of impact we want to have. At Adasina, we prioritize racial, gender, economic, and climate justice. Next, we choose the most effective investment instruments and tools (i.e., data, metrics, engagement, etc.) to address the issue. Last, we create an investment structure that best facilitates impact in our chosen investment universe. For Adasina, that is JSTC, our social justice ETF. |

How do we price this product? | Set the fees as low as possible, or as low as our competitors. | We will pay people with the skills to engage all stakeholders. We will base the price of the product on the costs associated with the outcomes we desire. |

What problem are we trying to solve? | Meet investor demand for ESG so we can gain market share from competitors. | Use financial markets to “move the needle” on social justice issues by changing investor, corporate, and government behavior. |

Who defines the problem and determines what is important? | Portfolio managers define the ESG “problems” that need to be solved. Gender Justice Example: | To define what is important, we look to communities most impacted by the issue we want to address. We work with them via our Social Justice Director who builds relationships and accountability between Adasina and social justice organizations. This is a paid position that does not exist elsewhere in the asset management industry. Gender Justice Example: |

How will we source and measure the impact data? | Financial analysts already on staff (this keeps costs lower) decide how to measure and search for appropriate data. Gender Justice Example (continued): | Again, we work with impacted communities and their social justice organizations, via our Social Justice Director, to define the issues, and source and measure the impact data we use. Gender Justice Example (continued): At the time, forced arbitration for sexual harassment was particularly harmful and common corporate practice that silenced victims, enabled perpetrators, and disproportionately impacted women, Black, and low-wage workers. |

What data will we use? | Asset management firms often use data they already have (this keeps costs lower) that is “close enough” to the issue to seem relevant, but does little to address real social ills. Gender Justice Example (continued): | Because we are solving for problems finance hasn’t usually addressed, we often cannot find an existing and genuinely relevant dataset, so we often partner with social justice organizations and create entirely new data sources. Gender Justice Example (continued): |

How do we measure success? | Financial returns that are similar to a traditional non-ESG fund. | In partnership with impacted communities. We measure success by the number of people positively impacted by systemic change we have a hand in making and by paying our own majority women and BIPOC employees a fair wage. Gender Justice Example (continued): |

Different Systems Produce Different Outcomes

Below are the outcomes of those systems as illustrated by comparing three global, all cap investment portfolios. First, the top ten holdings of a traditional (non-ESG) index, the MSCI ACWI Index. Next, the outcomes of applying a low-cost ESG lens, as evidenced by the top ten holdings of the MSCI ACWI ESG Index, an ESG index that many low-cost ESG funds seek to track. Compare the top ten holdings of these first two and you will notice some significant overlap. Last, the outcomes of our social justice investing process – the top ten holdings of Adasina’s Social Justice All Cap Global ETF (Ticker Symbol: JSTC). As you can see, different systems produce vastly different results.

Here you can see the low-cost ESG index holdings, which many low cost ESG funds seek to track, are extremely similar to a traditional non-ESG index, and without the impact benefits of robust shareholder engagement. These outcomes are not necessarily a result of bad intent, but because companies are trying to use the same old systems, and limited resources, to solve complex new problems.

I have an industry friend who consulted with one of the investment industry’s largest fund companies as they developed their first ESG fund. At the genesis of the project, there was an understanding of what it meant to have real impact and good intent from those involved. But, by the time the fund made it through the traditional cost-cutting systems of the company, the intended impact of the fund was highly watered down and ultimately looked indistinguishable from its peers.

Real Impact Takes Real Work

In addition to asset management, I do some work in the philanthropic sector. I’ve noticed that, while philanthropy has much that can be improved, one thing that they often get right is the resources needed for scale. When philanthropists think about funding efforts to make large-scale, systemic change in service of people and the planet, there seems to be a clear understanding that real impact requires extensive resources and funding. In investing, we often try to have a similar impact, but without funding the work. Is it any wonder we see complaints about rampant greenwashing?

Endnotes:

- CFA Institute, “ESG Investing and Analysis,” CFA Institute (2022).

- Morgan Stanley, “Sustainable Signals: Individual Investor Interest Driven by Impact, Conviction and Choice,” Morgan Stanley & Co. LLC & Morgan Stanley Smith Barney LLC (2019).

- Drew Voros, “ESG ETFs Looking Polluted,” ETF.com (August 26, 2021).

- “Greenwashing” and “impact washing” are terms used to describe the practice of providing misleading information so that an investment appears to have a greater environmental or social impact than it does in reality.

- Bella Private Markets, “Knight Diversity of Asset Managers Research Series: Industry,” Knight Foundation (2021).

- Francine D. Blau & Lawrence M. Kahn, “The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations,” Journal of Economic Literature, vol 55(3), pages 789-865 (2017).

- Neil Bhutta, Andrew C., Chang, “Disparities in Wealth by Race and Ethnicity in the 2019 Survey of Consumer Finances,” The Federal Reserve (September 28, 2020).